Epic Polar Expeditions to Inspire your Next Adventure

These Polar Expeditions serve as excellent reminders of the resilience, pure will power and desire to explore that is present in the human spirit.

Human feet have trodden on lunar soil. Human eyes have plunged into the maw of the Mariana Trench. We’ve stood at the greatest heights on our little planet. We’ve walked the lengths of our densest jungles. All to prove… what exactly? That we are resilient, defiant – alive?

Something draws out restless souls. It moves them to forge paths through untravelled wildernesses. It lures them to distant extremities. It breathes hard against their necks. We assume this thing is uncommon. Lesser-known. It’s reserved for those stubborn crazies who feel at ease in ocean swells and frozen winds. We make excuses for ourselves – explain away the urge to make more of life with talk of being too busy or too preoccupied.

Maybe it’s easier to think we’re not made of the same stuff.

The truth is none of us were made for defeat. We idolise those brave few because their stories are universal. They’ve responded to that suspicion we all have that maybe we could manifest a great adventure someday. A little more guts. Some more heart. Then there could be a few more explorers stepping out from amongst us.

In that spirit, we’ve compiled this list of our five favourite polar expeditions to inspire you to go further and to also showcase the mettle, endurance and imagination of this bold few, willing to take that first impossible step…

5. Polar Expeditions – Erik Goes To Greenland

An irrepressible Icelandic kid, by all accounts, Erik Thorvaldsson – or Erik ‘The Red’ (a possible nod to his fiery mane of hair) – was described in Icelandic sagas as the first permanent Norse settler in Greenland.*

Born in Rogaland, Norway, Erik was raised in an environment of unruliness. Aged 10, Erik’s father Thorvald was condemned for murder and cast out of Norway to settle elsewhere. Rather than choosing the safer options of Sweden, Denmark or Finland, little Erik was whisked off on a treacherous journey to a steep-faced Icelandic peninsula called Hornstrandir.

Years later, Erik married and moved inland to the valley of Haukadalur and (so the story goes) he built a farm there with his wife, Thjodhild, and raised four children (Leif, Thorvald, Thorstein and Freydis) – one of his sons, Leif, would later become the first Viking to travel the Vinland region of North America.

While his family turned and held fast to Christianity, Erik remained bound to Norse paganism. He adhered to his own laws and a seemingly secular sense of right and wrong. Like his father, Erik soon became an exile after a neighbouring farmer, Eyiolf, killed Erik’s slaves for causing a landslide that damaged Eyiolf’s property. In retaliation, Erik then killed Eyiolf and was sentenced to three years of banishment from Iceland. Erik found refuge on the Isle of Oxney and was again outlawed for a further three years after a murderous attempt to return to Iceland and steal back his setstokkr (an ornate beam his father had saved from Norway).

Around 982, during this time of exile, Erik took the Viking equivalent of a Year Out and sailed on a death-defying voyage to a far-flung land. His ship battled through North Atlantic storms and eventually rounded the rugged fingers of land called Cape Farewell. He reached an unknown western coastline, unladen with ice and stretching far and wide with scenery reminiscent of his native Norway. He spent the first winter on the island of Eiriksey, the next winter in Eiriksholmar, and then, for his final summer, journeyed north to Snaefell and Hrafnsfjord.

At the end of his exile Erik returned to Iceland with stories of his polar expeditions and of this distant land, which he called Green-land – a genius marketing ploy to draw in settlers from the colder, less hospitable-sounding Ice-land. Of course, many Vikings followed their new tourist guide and, in 985, Erik voyaged back to Greenland, joined by his fellow colonists. They lost eleven ships in the crossing. The fourteen that survived were hauled onto the shores of a new world, quickly expanding into two colonies spread across the southwest coast (what is now Qaqortoq and present-day Nuuk). They adapted quickly to their farmable surroundings and launched hunting expeditions to Disko Bay, inside the Arctic Circle, to find seals, walrus (they crafted various things with the ivory from their tusks) and the occasional beached whale. Erik became the leading chieftain and built himself a large estate on the boundless lands.

In the years that followed the colonies grew to around 5000 inhabitants. These polar expeditions spilled out into Eriksfjord and alongside the many other fjords nearby, until one huddle of incoming Icelandic immigrants brought in an epidemic, killing many unsuspecting colonists, including Erik.

*Historical accounts vary – some claim the first Norseman to reach Greenland was Gunnbjorn Ulfsson, who first sighted the land-mass a century earlier. He referred to the land he sighted as Gunnbjorn’s skerries. However, he did not settle, or perhaps even land, there. There was also Snaebjorn Galti, in the early 10th century, who accidently happened upon these far-out lands west of Iceland. However, his attempt to colonise the eastern coastline ended in chaos and he was killed in an uprising and his saga has been buried by the centuries.

4. Polar Expeditions – 94 Days In Antarctica

Raised in rural Minnesota, Ann Bancroft is widely regarded as a legend of polar expeditions. The first woman to complete many journeys in the Arctic and Antarctic, she was raised in what she described as a family of risk takers. In her early academic life she struggled with a learning disability, although she went on to graduate from St. Paul Academy and after that taught physical education, doubling as a wilderness instructor, and, generally, as an all-out force of nature. She resigned from teaching in 1986 to participate in the Steger International Polar Expedition, travelling to the Ellesmere Island, The Land of Muskoxen, on March 6th and arriving by dogsled, 56 days later, at the North Pole with all five of her team members.

In 1992, Bancroft led the first team of women to ski across Greenland. In November that same year she led three women on the grassroots-funded American Women’s Expedition to Antarctica. It took 67 days and they covered 660 miles. By early 1993, they had become the first women’s team to reach the South Pole on skis.

Bancroft was then the first woman in history who had stood on the top and bottom of our planet, at both poles.

In 2001, after 2 years of intensive training, Bancroft flew back to Antarctica with fellow polar explorer and Norwegian endurance athlete, Liv Arnesen, to take on the challenge of their lifetimes – a 1717-mile trek and ski across the world’s driest, most inhospitable continent. Arnesen was the first woman to ski solo and unsupported to the South Pole. She had also climbed the north side of Mount Everest. Both women had enough experience to make independent attempts at being the first woman to sail and ski across Antarctica. However, instead of engaging in that typically masculine activity of a polar race, Bancroft and Arnesen quashed the competition and set off on the adventure together.

Two teachers – Arnesen had taught for 20 years at a high school and college, as well as assisting in the rehabilitation of drug users – united on a mission to lead by example, inspiring children the world over to pursue their lifelong ambitions.

“We want to expand the walls of the classroom through our journey.”

Travelling by sail and ski, the two veterans began their transcontinental crossing, trudging and sliding amongst frozen volcanoes and crevasse-strewn ice fields as they inched their way across the landmass. At the beginning they were hauling 250 pound sleds, and, as the journey evolved, they faced winds of up to 100mph and temperatures that descended as low as -30 degrees F.

94 days later, on March 21st, the Bancroft-Arneson Expedition ended when both Bancroft and Arnesen emerged and lay their withered sleds to rest. They had covered roughly the distance from LA to Chicago in nigh-insurmountable conditions. On February 19th they were airlifted together from McMurdo Station, utterly drained, but triumphant.

In 1995, Bancroft was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. Two years later she founded the Ann Bancroft Foundation to offer support for girls in her hometown of Minnesota, funding a combination of mentorship, grants and programs.

In an interview with Climate Generation, Bancroft was asked what she hoped the legacy of her expeditions would be – “My basic hope for our polar expeditions is to move people into engagement. I want people to feel empowered to take the small steps that, just as in an expedition, will help us reach our goal…”

3. Polar Expeditions – The White Darkness

In 1907-09, Ernest Shackleton set out on his Nimrod expedition in a bold, but ultimately unsuccessful, attempt to reach the South Pole. His most loyal companion, Frank Worsley, had read the following line as a kind of opening salvo: “Men go out into the void spaces of the world for various reasons. Some are actuated simply by a love of adventure, some have the keen thirst for scientific knowledge, and others again are drawn away from the trodden paths by the ‘lure of little voices,’ the mysterious fascination of the unknown…”

Henry Worsley was a descendent of Frank Worsley and a great admirer of Shackleton. He was also raised on stories of his father, Richard Worsley, who fought with distinction in World War II and led regiments in various theatres of war, from North Africa to Italy.

Get wet: you die

In 2015, Worsley was 55 when he attempted a solo, unsupported and unassisted crossing of Antarctica. Messages were painted on his skis from his family and his wife, Joanna, who’d written – “Come back to me safely, my darling.” She knew exactly why Worsley wanted to do this and understood entirely that he had unfinished business with the frozen continent. In fact, she often referred to Antarctica as Henry’s ‘Mistress’. And a cruel Mistress she was indeed, as Worsley had learned from several of his past expeditions, which strengthened his resolve with simple yet crucial lessons, like “Get Wet: You Die”.

71 days into his journey, Worsley was suspended on a large ice dome on the Antarctic peninsula, called Titan Dome. He was trapped in a whiteout, pushing to the domical peak and the inevitable downhill waiting thereafter. It wasn’t far, but he was totally drained and suffering from intense stomach pains. His iPod had broken, leaving him in perpetual silence and a visceral isolation in the infinite white darkness. The air was hardly thick enough to breathe and his diary entries revealed the strain of a mind in extremis – “So breathless,” he wrote, “I am fading…”

Urged on by his family through his darkest hours, Worsley was lifted by messages from his children and his wife. “I owe them everything,” he wrote in another entry at that time.

On January 22nd, 800 nautical miles from the start of his journey, Worsley finally pushed the button calling the world’s most expensive taxi ride. After days of pushing on he eventually admitted that he, like his hero Shackleton, had ‘shot his bolt’.

When the rescue plan landed, he walked on his own power and boarded from the ice with irresistible cravings for a cup of hot tea. He was a mere 109.5 nautical miles from his journey’s end on the Ross Ice Shelf. Tragically, the following day, Worsley’s wife Joanna was informed that he had been rushed into surgery, suffering from bacterial peritonitis. First his liver failed. Then his kidney. Before Joanna could board her flight to Punta Arenas, to see her husband, the British Embassy gave her the news that Worsley had died.

A year later, Worsley’s close friend, army captain and fellow Polar explorer, Lou Rudd, and extreme endurance athlete, Colin O’Brady, took a flight to Antarctica in the stomach of a Russian Ilyushin II-76MD. Rudd had set out to finish what Worsley started – the long overdue fulfilment of Shackleton’s enduring dream. Among his painstakingly refined essentials, Rudd carried a flag bearing Worsley’s family crest.

It was his intention to deliver the flag to the finish line, completing a solo, unsupported and unassisted crossing of Antarctica on human power alone.

For 56 days, the two men hauled their Norwegian pulks (weighing in initially at 300 pounds), sometimes spending up to 12 hours in their harnesses. Rudd consumed around 10,000 calories a day, surviving off freeze-dried meals, protein shakes and porridge. O’Brady broke his days down into 8 90-minute stretches. Whereas Rudd cut his days into 9 chunks of 70 minutes. As he skied, Rudd dug into a grazing bag filled with chocolate, nuts, fruit pastilles, salami and frozen cheese, which he tucked into his cheek and held there like a hamster. For company – and to distract himself from frozen spin-drifts, blinding whiteouts and exhausting sastrugi – he delved into audiobook biographies of Winston Churchill and the music of U2 and Pink Floyd.

Moments of reprieve were few and far between. On several days Rudd sighted rare parhelions wrapped around the sun – halos of frozen ice crystals. Another day was uplifted by a miraculous moment when a white snow petrel suddenly appeared 10 feet in front of Rudd. It was a baffling encounter and an unexpected treat to see wildlife in such unforgiving conditions. When he recorded his audio log that night, Rudd explained: “It was around about two o’clock… I caught something moving out of the corner of my eye and I looked up. It was a bird in front of me. Pure white. A stunning bird about the size of a dove, with a little black beak… I’m not a particularly spiritual person, but if ever there was anyone coming to pay me a visit and have a look, that was it… I really enjoyed that. If it was someone, I know exactly who it was.”

The only other encounters with life were at the scientific South Pole base, which both explorers passed through. Rudd lingered at the base for just an hour and then continued on the last leg of their 925-mile expedition, two days behind O’Brady.

It was a gruelling two month race, recalling that bygone era, over a century earlier, when Amundsen and Scott had raced each other to the South Pole.

The day before the end of his journey, on December 27th, 2018, Rudd wrote in his diary: “My number one priority was to come out here and ski solo, unsupported and unassisted right across the continent and by the end of tomorrow, I’ll have done that… it’s a minor miracle that both of us have completed a journey that’s been attempted before, nobody’s ever managed it, and then, lo and behold, in one season two of us attempting it… I’m really pleased for both of us. Where I’ve come – it’s just a title thing. It doesn’t mean anything to me, first, second. It’s just a title. What matters is that I’ve completed my expedition, and that’s the bit that’s really important to me.”

Finally, O’Brady reached the Ross Ice Shelf and Rudd followed close behind him. The two men sat together on the open ice plains in the relative tropics of -10. They joked around and took photos and pitched their tents 10 feet apart and shared supplies buried in the ice a year earlier, which included coffee and milk powder. They feasted there like Polar Kings, until 5pm on 31st December, when a Twin Otter plane descended into view, promising to deliver them back to civilisation.

2. Polar Expeditions – Amundsen and Scott

The two names that first come to mind when you mention Polar Expeditions – Norwegian Roald Amundsen and Brit Robert Falcon Scott were at the top of their experience. Hardened by years of expeditions. Inured to the cruelties and shifting moods of remote places. Entirely ready to engage in a breakneck race to be the first man to stand at the South Pole.

In mid-January 1912, 43-year-old Scott was 800 miles into this historic journey. He and his five-man party had been subjected to weeks upon weeks of blizzards, increasingly severe frostbite, and, of course, the endless burden of trudging their sleds across the ice, wrapped in the endless white vistas, en route to the geographic South Pole. They were optimistic. After a day’s hard grind of 5 miles Scott sat in his tent and wrote in his diary that their chances still looked good. They had less than 80 miles to go.

The world looked on. As far as they were concerned, the question of first or second remained unanswered.

Meanwhile, 39-year-old Amundsen was already returning to basecamp, having planted the Norwegian flag at the South Pole and claimed the prize for his nation. It should be noted that Amundsen did have a few advantages. He camped at the Bay of Whales, located on the Ross Ice Shelf, and began his journey 60 miles closer to his prize than Scott, who lingered in the western reaches of McMurdo Sound, with certain scientific obligations. Whereas Amundsen was there with a single, solitary focus: to reach the Pole and return home safely. He was also a veteran of polar hardship and extreme toil in worldly hellscapes – the first man to sail the raging Northwest Passage, where the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean meet in a wash of roiling black waves and drifting ice floes.

In early 1911, advance caches had been laid with food and all the essential supplies needed to hunker down during the Antarctic winter. Amundsen pushed early and set out in September that year, but was forced to turn back and rush to camp when temperatures descended to a mind-shattering 68 degrees below zero. He began again on October 20th, when the conditions permitted travel, and began his long, arduous sprint into the history books. Scott followed on November 1st, using Manchurian ponies to bear some of the load, as well as sled dogs and motorised tractors. The ponies soon grew weak from the cold and were shot by the crew. The sled dogs had to eventually be sent back to the camp. While the motorized tractors caused numerous problems and often broke down. In the end, a large amount of the work was done through man-hauling and trudging on foot over the wide ice fields.

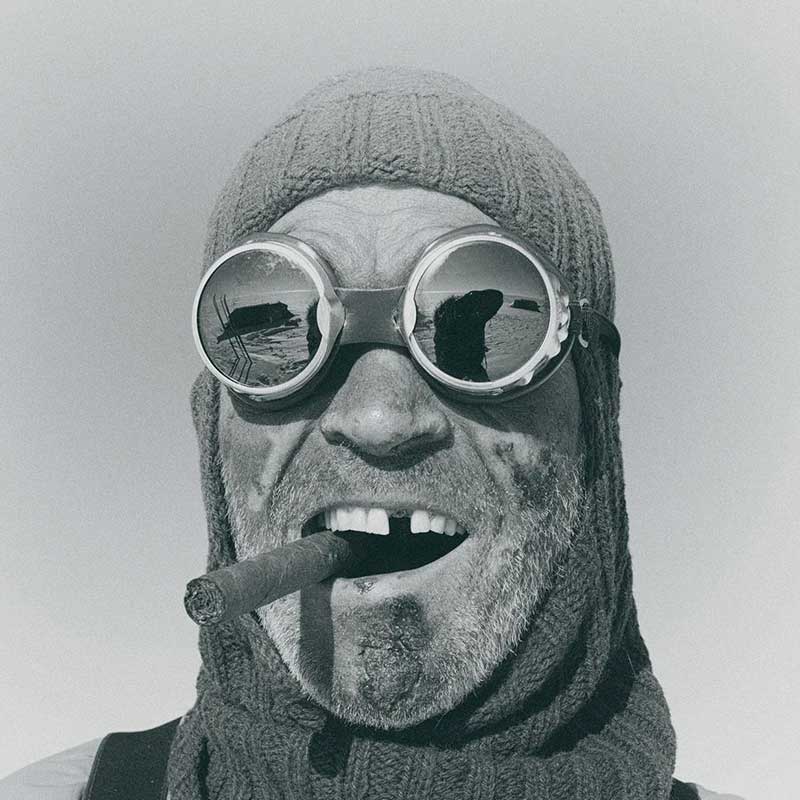

By contrast, Amundsen and his Norwegian team took an untried route through a labyrinth of mountains, crevasses and glaciers. They stuck to a combination of skis and sled dogs (the explorers later killed and ate the weakest dogs) and travelled quickly across the tundra at a pace of over 20 miles a day. On December 14th Amundsen arrived at the South Pole. The first men to reach the heart of Antarctica, they dug the Norwegian flag into the snow and ice and shared cigars and took photographs.

They stayed there only a few days before turning back for the long trek to basecamp.

Meanwhile, Scott and his British team battled on, but didn’t find the pole until January 17th, 1912. There they found the remains of Amundsen’s camp. It was late in the Antarctic summer and temperatures were about to drop. Quickly the men turned back and left the Union Jack and the Norwegian flag fluttering there together, lonesome scraps of colour in a white abyss.

They journeyed back north, frostbitten, malnourished and intensely disappointed for not having been the first. 20 days thereafter, Amundsen re-emerged at the Norwegian base camp, on February 17th. While the Norwegians celebrated on the coast, the British were still being punished inland, where conditions had only gotten worse. Edgar Evans was the first to succumb to the cold. Then the badly frostbitten Lawrence Oates died a month later, stepping out late one night into a blizzard, so he could no longer slow down the team – his final words are etched across the encrusted surface of polar history: “I am just going outside and may be some time.”

For several more days, Scott, Edward Wilson and Henry Bowers huddled together and fought on as temperatures fell and the blizzards intensified. They were a mere 11 miles from the next supply depot, but unable to keep moving.

All three men perished in their tent – “We shall stick it out to the end,” Scott wrote in his diary, “But we are getting weaker, of course…”

1. Polar Expeditions – The Endurance

Often described as the greatest survival story in human history, The Endurance Expedition is a controversial explorer’s favourite in one regard – on the other side of the continent, a ship called the Aurora sailed through the Ross Sea and landed at Scott’s old haunts in McMurdo Sound. The Aurora crew’s mission was to lay depots along the ice shelf for Shackleton’s party to pick up as they crossed Antarctica. They also had a programme of scientific and photography work. Of that party, three died, including the ship commander, Aeneas Mackintosh. This fact will become relevant later on, though we feel it doesn’t foreshadow the achievements of Shackleton and his loyal crew.

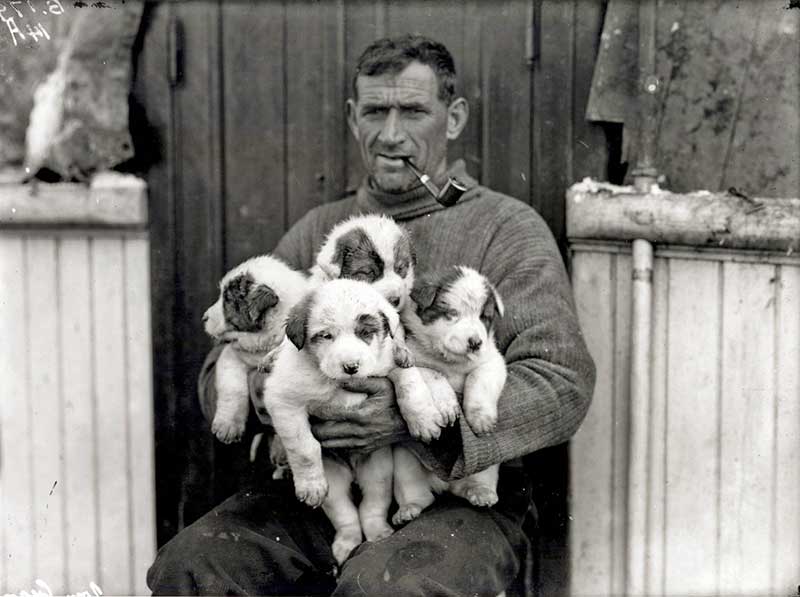

The story of the Endurance will never be forgotten. A stubborn, gritty morsel of polar history, carried by characters like Shackleton himself, the sled dog-lover Thomas ‘The Irish Giant’ Crean, and the Navy-trained Kiwi, Frank Worsley. It remains a salient example of human potential, even under the permutations of extreme peril.

Shackleton’s crew of 27 set off in 1914, summoned to fulfil a dream of being the first explorers to traverse the Antarctic continent in its entirety. Shackleton had served in the merchant marine and was no stranger to Antarctica’s many moods and tricks. In fact, he’d even been part of Scott’s previous attempt to reach the South Pole, in 1901. On November 2nd that year, summer light had broken over the horizon and Shackleton, Scott and Edward Wilson began to trudge the 800 mile dark-ward trail to the untrodden pole. They quickly descended into bouts of Polar glare, hunger, scurvy and frostbite. By December 31st, the following year, Scott finally gave the order to turn back and abandon their prize – Shackleton admitted he was ‘broken’ and was coughing up blood.

During that expedition, Shackleton learned of Scott’s tendency to berate and bully his men. He and Scott argued bitterly on several occasions. So, when it came time to choose his own crew, he sought qualities that he himself valued most highly: optimism, patience, physical endurance, idealism and courage. Shackleton found all these things in the broad-chested, 42-year-old New Zealand seaman Frank Worsley, who he appointed as captain of their 140 foot wooden schooner, christened the Endurance.

The crew set sail from the warmer climes of Argentina on October 26th, 1914. Winston Churchill had already permitted the men to avoid service in WWII and ‘proceed’ with their expedition – what Shackleton described in his diary as the ‘last great Polar journey that can be made’.

10 days later, the Endurance party drifted onto the glacier-edged waters of South Georgia, 1100 miles east of Chile’s Cape Horn. This was the Gateway to the Antarctic, an island of ramshackle whaling stations with few inhabitants and the last taste of civilisation before the long journey… South!

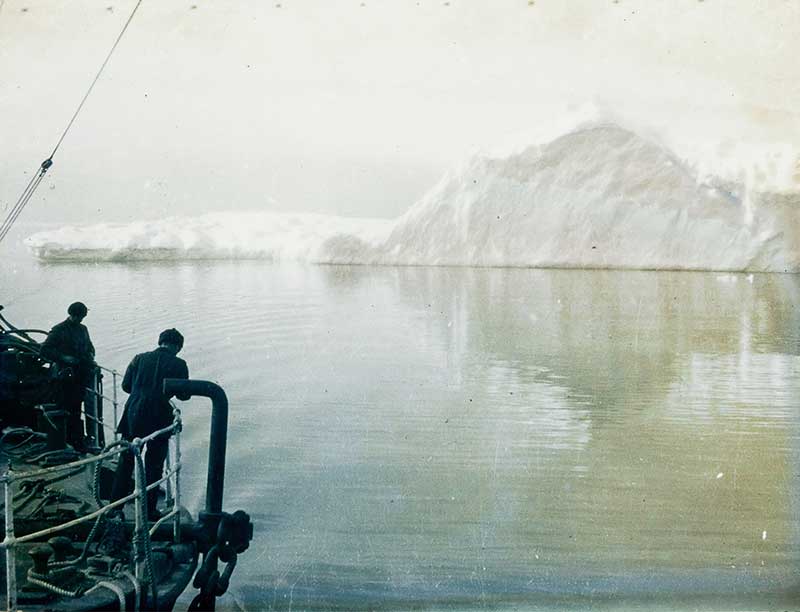

On December 5th, the Polar Expedition party crossed the Weddell Sea, which was heavy with pack ice and bergs. They snaked steadily through the frozen obstacle course and sought the sure ground of the Antarctic coastline, where they could wait out the winter before beginning their long trek over the continent to the distant ice shelves carved by the South Pacific Ocean, and, beyond that, the warmer climes of New Zealand.

However, on January 18th, 1915, the Endurance drew to a halt in the encroaching sea ice and became lodged in an ice floe. The crew was imprisoned onboard. Winter was fast approaching and they were icebound, totally alone and still many months from the warmth of the November melt. Yet their spirits were buoyed by Shackleton’s leadership. There were no hierarchies. Everyone had the same rations and the same share of chores. A sense of fellowship was palpable. The men called Shackleton ‘The Boss’ and he moved amongst them with ease and warmth and rarely erupted with anger. Indeed, as one crew member later noted, Shackleton ‘[erred] on the side of over familiarity’ and even bore slight shows of disrespect. He was Scott’s polar opposite. Cheeriness and optimism ruled the ship. The men played poker games, enjoyed Sunday phonograph sessions and once a month even shared a lantern-lit meal in the dining room, which they called the Ritz. Then photographer Frank Hurley would present slides of his travels around the world in places like Java, crowded with palm trees and Indonesian beauties and all manner of things that must’ve seemed so terribly alien to the crew.

On October 27th, disaster struck… The Endurance hull cracked as the ice pressure constricted inwards. Water found ruptured seams and the frozen berths began to flood. Desperate, the men made vain attempts to drain the bilge, but the ship was quickly dismantled and angled up towards the eyeless ether as the Endurance began to sink.

The Endurance party lowered the lifeboats and provisions onto the surrounding ice. Suddenly they were marooned. Sitting over a 1000 miles southwest of those incandescent whaling lights on South Georgia Island, they watched together as their wooden lifeline was unceremoniously crippled and bent inwards, disappearing into the ice. There was no way they could signal for help. So they trekked on foot and with sled and carried the lifeboats, each weighing close to a ton. The weight was too much and they were forced to stop and set up camp on the ice. They slept with fears of orcas breaching and breaking the ice and sometimes their cold bed-floor would crack and sleeping bags were often drenched in the freezing water. They called this temporary shelter Patience Camp – a frozen island adrift on the perishing Antarctic water.

During this time, Shackleton kept things civil by staging football games on the floes and keeping three of the most unruly characters in his tent.

Despite the frozen hell around them, there was only an occasional whisper of mutiny

The Endurance party stayed in Patience Camp until April 9th 1916, when the floes began to groan and crack and melt away – it was finally time to launch the boats.

A week later they reached a desolate scrap of rock called Elephant Island. Shackleton’s crew, including its weakest and most frost-bitten and sullen members, made their camp under upturned lifeboats. While Shackleton himself led an 800 mile voyage in the remaining boat to find help. He took with him only five others, including Worsley and Thomas Crean. They fought the far-out frozen winds and lashing waves and the open ocean and emerged soaked and with little food, on May 10th, at South Georgia Island. Shackleton’s Five then continued on a trek of 26 miles over glaciers and down waterfalls, until they found a whaling station and a totally bemused group of onlookers.

Shortly after making landfall and gathering a rescue party on South Georgia, Shackleton returned to Elephant Island and saved the men they’d left behind. Given every opportunity to abandon hope and dignity and fellowship, Shackleton had gritted his teeth and forced a smile and guarded his virtues.

Reflecting on all that they’d been through, Shackleton wrote that they had ‘reached the naked soul of man’.

The fact remains – of those who were under Shackleton’s direct command, not a single life was lost. As polar expeditions go, it was a feat that is still, to this day, one of the most unimaginable stories of human optimism, courage and perseverance ever told.

Feeling inspired? Why not find your dream location to watch the stunning northern lights, or plan your next kayaking trip in Scandinavia.

Comments are closed.